3

3

Luis Buñuel

| Movies Home |

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeois (1972)3

Luis Buñuel

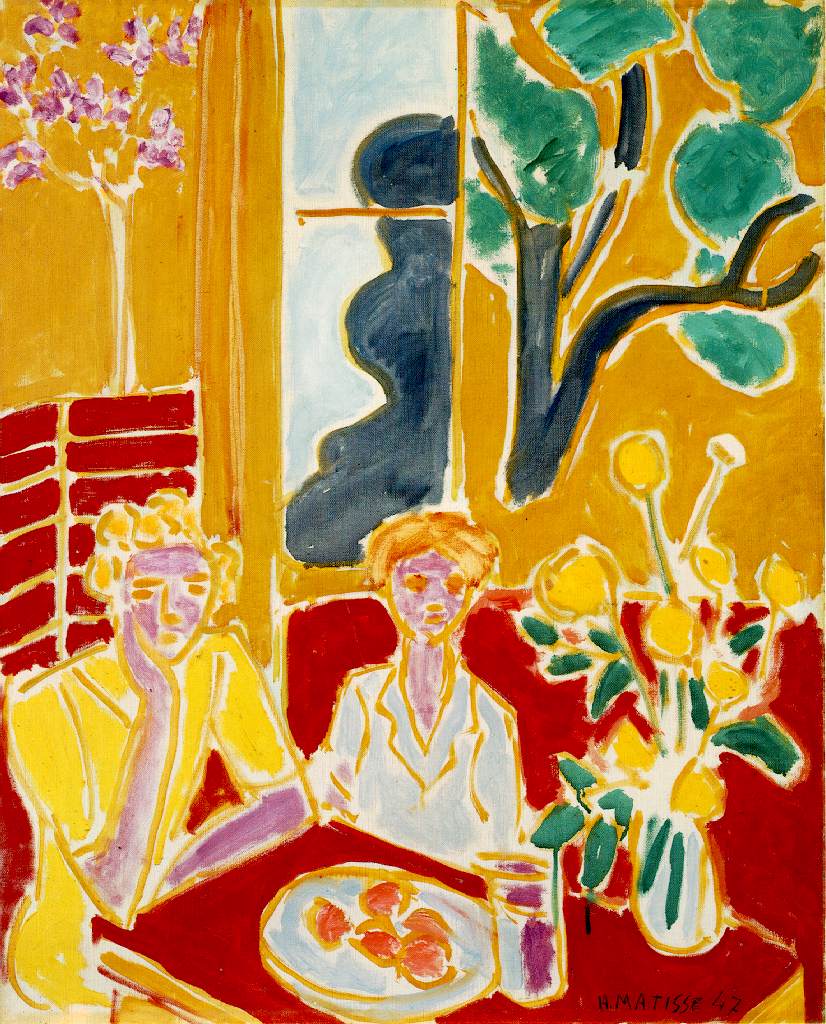

Haven’t you ever wondered what would happen if, just once, a a great artist were allowed to evolve to the later years of life,? What untold genius would result? Well my friends, there is an answer to that question, and his name is Luis Buñuel. La Belle Du Jour, Diary of a Chambermaid, Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, That Obscure Object of Desire. These are not bad films. Shot in glorious French 1960s Technicolor, Discreet Charm is a masterpiece. It’s enthralling. There’s a scene with a waiter that looks just like Tom Snyder. I said it was enthralling. Like any Buñuel film, it tackles the bourgeoisie, the church, men, women—the military. It has enough surreal twists and turns to shake a stick at. Although I wouldn’t. And it has a pervasive and paradoxical (because it’s so bright and colorful) melancholy which leaves you feeling both empty and full. Was that just a load of crap? Whatever. Anyway.

Let’s talk about the humor. Grand Master B’s humor is unusual in the way it sneaks up on you. Many of the jokes are weird. It felt as though I was watching it on one side of the couch, my brain on the other. I was busy reading the subtitles and trying to figure out what was going on, while my brain was over there just cracking up at everything. Sometimes I wanted to ask my brain what was so funny, but he would have said, “It just is” or perhaps told me to “Shut up, I’m trying to watch the film.” The lessons are complex. You feel as though you’re probably only getting ½ of the point at any given time and that repeated watching would add up to the other four or five halves.

So many memorable moments. I won’t belabor the obviously funny ones, those involving animal lust, the bishop as gardener, the dialogue, the film. But what about the waiter (a young Peter Jennings?) dropping the ducks, which suddenly are props? And the way he then places them back on the tray with quiet callousness. Every bit as dark and disturbing as the dream sequences of the emotionally disturbed army officer. Technicolor blood packets. You won’t see that in To Catch A Thief.

The film is a tour of color. The blood red window frames against the white walls of the couple’s country home during the “love in the bushes” scene and again in the aforementioned Tom Snyder scene. Real, not real. Real, not real. And so on. Buñuel, like Mies, is the man. Real. Not real. Real. Not real. Real. Buñuel is the man.