And then . . . the whole thing starts over: The guy repeats the entire set, gestures and all. Only this time a recording of the set he just did, snorts and groans included, is layered over his performance with a slight delay—and suddenly you realize that the joke’s on you. This time there’s more clapping. But then . . . it begins again—and again.

In Bruhaha, 1998-99, performed in Malmo, Sweden, and New York, Olav Westphalen repeats the same set eight, even sixteen times, until you can’t tell the difference between the live and the taped, the spontaneous and the rehearsed, the joke and the “comedian.” This cacophonous micro-opera of failure has no fixed boundaries. Yes, the crowd laughs once it gets what’s going on, but as Westphalen moves from canned comedy to aggression to shameless flattery to total self-destruction, we lose any precise sense of where the joke begins and where it ends, and who its real “butt” is. There’s something going on here that’s not funny at all.

The joke’s true target is the well-worn irony that has become the badge of art-world belonging. The ironic pose typically adopted in the appreciation and consumption of abjection and various forms of reservedness is for Westphalen the mechanism by which the viewer guards himself against the very sense of failure and absurdity artists like Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley began foregrounding in the ’70s. To use the language of Baudelaire’s 1855 essay on the nature of the comic, the “laughter of relief” buffers the self from the pathos of the other man-the one who falls and splits his face open on the cobblestones, for example. What Baudelaire called “the absolute comic,” on the other hand, shatters the pretension to superiority of the one who laughs at the spectacle of the other’s misfortune (as he realizes that he too has already or will someday fall and break his face). Only when both men are on equally abject footing does the comic achieve the truly grotesque-and the truly grotesque flies in the face of the kind of ironic detachment that second-rate contemporary art so often solicits.

For Westphalen, who pitches his practice at that border between art and life pioneered by Allan Kaprow (with whom he studied in California) and further explored by LA performance artists such as McCarthy, Kelley, and Chris Burden, abjection and comedy raise key questions for art today. Like Kelley, Westphalen views caricature and the comic as anti-authoritarian and anti-idealist aesthetic practices, a gauntlet thrown down in the face of the “serious” tradition derived from Minimalist. Yet unlike Jim Shaw, say, Westphalen isn’t interested in celebrating American trash culture for itself; he isn’t interested in affirming “the low” or promoting other anti-art strategies—even as he endorses their suspicion of beauty. Indeed it’s the impossibility of arriving at “real life,” the “everyday,” the “ugly,” the “abject,” and, ultimately, the “political” that is dramatized and rehearsed in his art—an impossibility whose possibilities have not been adequately recognized and mined.

Instead, Westphalen sees these terms as formalized aesthetic codes, fully integrated into the language of contemporary art and thus in need not simply of deployment but careful study. Meet the Tigers, 2001, a video in which Westphalen suits up to play with a professional Swedish ice hockey team, is less an actual replay of abject skill-lessness and the rough- hewn, untrained aesthetic that has emerged as a dominant strain of American art in the ’90s than a catalogue of such displays of artlessness. Westphalen is here exploring the language and representation of exteriority rather than performing any authentic dumbness, stupidity, or weirdness. Westphalen dons his hockey gear, is toyed with in a warm-up scrimmage, and gets brutally checked; when he plays goalie, we see him barraged with pucks until he takes one in the mouth and is “forced to swallow it.” But all this can only be an image of pathos, suggests Westphalen: The artist qua artist can never be pathetic by performing pathos. That takes a further turn of the screw.

If Westphalen is out to puncture the pretension to “outsider” status, it’s not so much to take any specific artist to task but to call attention to the structural nature of the dialectical reappropriation of the “outside.”

Tree House, 1996, built by a group of volunteers In a forest outside Kassel, Germany, then laid—tree and all—in front of the Fridericianum, the birthplace of Documenta and a mecca of social sculpture, gives a new twist to the term platform, so central to Documenta11’s claim to stepping outside the authorized zones of aesthetic presentation and consumption. A trope of childhood autonomy, the tree house nevertheless signals an autonomy wholly sanctioned by parental authority. Westphalen’s mode of caricature never merely mocks; It always presents an insight into Its object.

His drawings are a codex of such disclosures. In “Roadside Signs,” 1998-99, which transform intellectuals into fodder for American highway signage—Lacan’s Grill and Lounge, “Big” Foucault’s Trailer Parks, and Borges’ Bar-Restaurant—Westphalen points to the manner In which ideas are reduced to commercial tags across the cultural landscape and thus to the limits of translating theories Into art.

1 Mark, 2001, along with his ungainly reproductions of Andreas Gursky’s famous panoramas of global capitalism, Rhine, 2001, Prada II, 2002, and Atlanta, 2001, are not mere parody, but rather attempts to reveal the streak of nostalgia that inheres In the memory of the “mighty German Mark” and German art’s renewed investment in the Kulturkritik rejected by Adorno In the ‘30s for secretly affirming the culture It purportedly sought to criticize. If art, here, takes the guise of the one-liner, It nevertheless flaps Immediately Into a serious reflection On just What kind Of criticality Is possible In caricature. In Illegally imaging the watering-down that Is part and parcel of cultural translation, Westphalen points to the pathos of art Itself. If art can’t laugh at Itself, then what good Is it? one might ask.

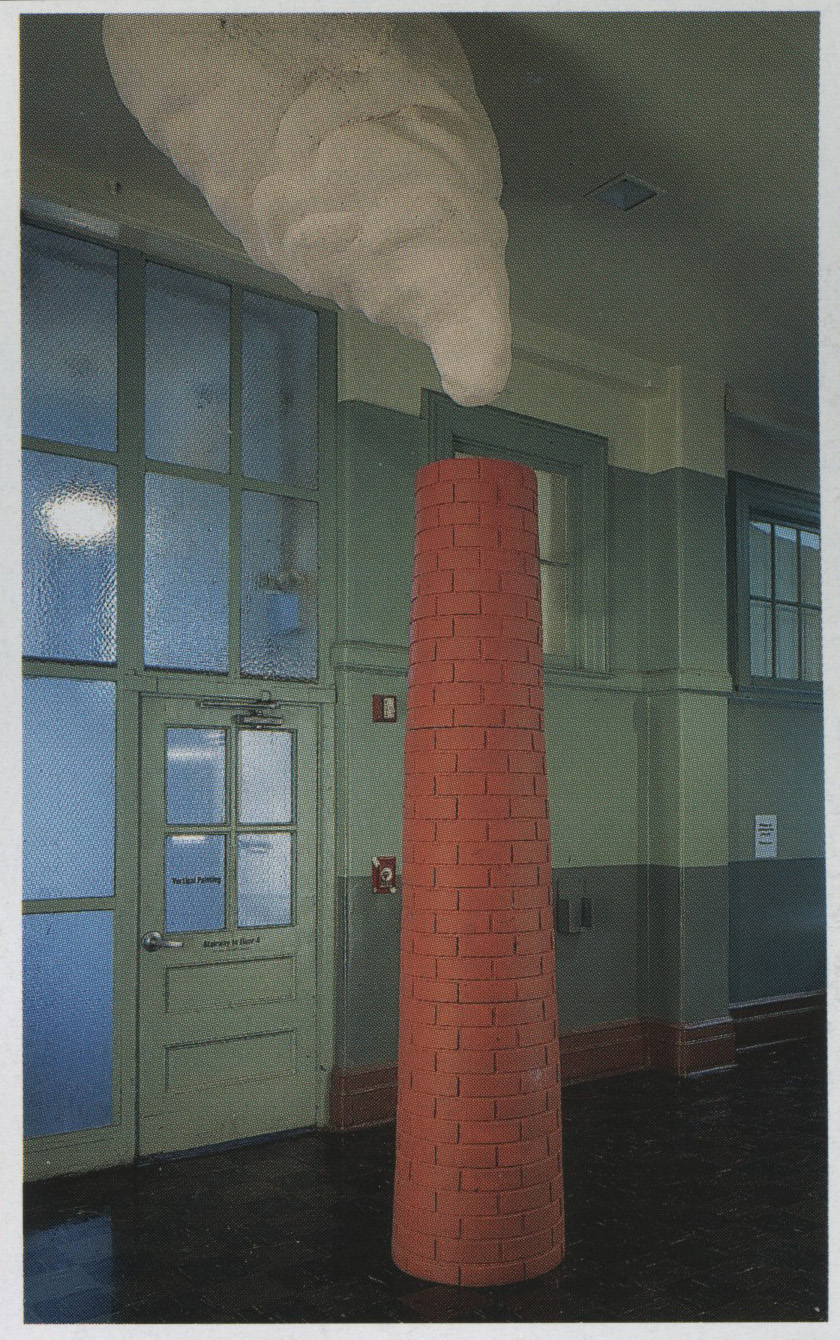

Two recent sculptural projects also explore these Issues In a three-dimensional context: Smokestacks, 2000, several large nail-polish red brick stacks the first of which was shown at P.S. l’s “Greater New York” exhibition, and E.S.U.S. (Extremely Site-unspecific sculptural), 2000, an unlikely cross between an Ed Wood-worthy UFO and a Weber grill, shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Phillip Morris, Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Tompkins Square Park, and elsewhere, remand us just how paradoxically universal the Idea of site-specificity has become and how it blends itself to the Inherently fantastic—dare I say cartoonish?—nature of art that Pop placed front and center. Both works are quite literally parasites, eating away at the attempt to liberalize space and place in notions such as objecthood and site-specificity. More seriously, perhaps, both works attempt to come to terms with an idea that Minimalism and Conceptualism found difficult to tolerate, the idea that art may not have much of a place at all—that it’s neither a “specific objects,” nor a specific site—and that, just perhaps, this is the source of both its weakness and its strength.

In other words, suggests Westphalen, a truer image of art’s possibilities might be the following: A guy wearing an unkempt wig and thick glasses steps out from behind the red curtain into the spotlight. He smiles nervously, clears his throat, and launches into a joke. Silence. He blurts out another one. And another . . . Saul Anton is a New York-based critic.