Architecture is the battleground between what needs to be and what could be. And this is why I care about it. Now, anyone who is already or is studying to become an architect should please skip to the next thing. There is nothing for you here. Really. I promise. Everyone else, please: My favorite dichotomy in everyday architecture has to be that age-old problem of form versus function. Form would include anything to do with the aesthetic. Function would be anything to do with the people who actually use the building. It seems inevitable that these two elements will often find themselves very much at odds. I imagine the relationship follows something of a protocol, like paying taxes. You start by sending the government a huge wad of money. This would be function. And then whatever small sum you’re lucky enough to get back—is form. It may not be much, but you should at least get something. And function will not go unchecked.

If it did I think we would all be in a world of hurt. For example, if economy of space were the only thing that mattered, I’d expect every building would be a giant cylinder, and a college campus might be happily mistaken for a petrochemical plant by a bird, or say, cruise missile. Students will work much harder knowing that each lecture could be their last.

Though many happy compromises have been reached, it is those buildings or elements of buildings in which the aesthetic prevails that most move people who are moved by these things. Frank Lloyd Wright’s works illustrate the triumph of (his) aesthetic with their frequent walls and narrow passageways that are anything but conducive to human traffic. But then of course this is not the usual efficient way. And so whenever there is an extra detail that might otherwise have been left out, or a carefully planned inner space that could not possibly be of any use but to the imagination, this is man taking stock of his basic drive to churn out more widgets—cheaper, faster—to save on heating—and saying, “Aww, screw you.” I love it, and just knowing someone has fought the good fight, I can now turn happily back to my cubicle—away from windward. On the other hand, not every decision need be a battle, such as the brand of roofing shingle or the width of a chimney. The architect must pick and choose his battles. Ariel Sharon prefers to move on terra cotta.

Another point is that it’s often not easy to tell between form and function, just which is which. If a building is supposed to be a place of learning, like a library or lecture hall, then surely, a high ceiling plays a key role in allowing thoughts to expand in one’s head. Oh, and by the way, it’s pretty. In this instance, form and function are essentially doing the tango. And if the spire of our local church gets us that much closer to God, then the dome at St. Peter’s puts Italians right up under God’s behind. A castle wall must be very thick. Can you see the beauty in all ten feet?

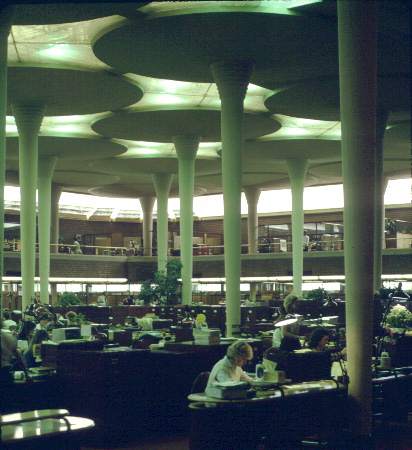

And then there is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax building with its leaking roof and giant concrete lily pads for lights. Those looming lily pads may portend distraction, but nothing could be further from the truth. With their spiritual and artistic needs automatically satisfied by the lily pads, the workers are now free to devote all of their attention to their work. One would think having to put out buckets whenever it rained would be an annoyance, but it’s said the Wax employees loved their building in spite of it all—and wouldn’t have changed a thing. Wax warriors, I say.

So those are the forces that define our relationship to architecture. But it is on the general perception of a structure where Robert Frost picks up the thread:When Robert Frost read a the institute of Modern Literature at Bowdoin College earlier in the year he suggested, in passing, a new method of instruction, employed by him at Amherst, which he would like to see in more general use in the colleges and which he has taken with him to his new post at the University of Michigan. "Education by presence," he called it, pausing then only to emphasize the obvious effects upon university students of the mere presence among them (upon the campus) of leading scholars in major lines, even if those leaders never took textbook in hand to conduct ordinary courses of classroom instruction.

"My greatest inspiration, when I was a student, was a man whose classes I never attended. The book that influenced me most was Piers the Plowman, yet I never read it."

"What I am saying is that there are and always have been three ways of teaching, namely, by formal contact in the classroom, by informal contact, socially as it were, and by virtually no contact at all. And I am putting the last first in importance-the teaching by no contact at all."

I don’t know whether Frost is totally serious here or not, but his point is well taken. "Education and inspiration by presence." Essentially, this is sort of an argument for the need for great architecture in cities, on the campus, or for that matter, anywhere learning can be afforded.

We have this great building in the middle of our campus, which I’ve never actually been in. In fact, I’ve never actually seen it. I’ve never seen a picture of it. I don’t even know who did it. But just knowing it’s there or knowing that others know it’s there, particularly those who didn’t get in, is reassuring. But now these visiting scholars from Kobe have called into question the width of its main entrance. Of course, they realize, this means war.